Hello,

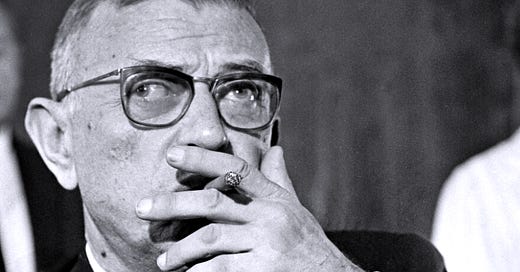

What comes to mind when you hear the name “Jean-Paul Sartre”?

Paris intellectual smoking and arguing his way through the day at Café de Flore with his lover Simone de Beauvoir?

Apostle of existentialism whose views led to the moral relativity of our times?

Refuser of the 1964 Nobel Prize for Literature?

His relationship with De Beauvoir is fascinating, and his Leftist politics are interesting (although they haven’t aged well).

But it’s Sartre’s magnum opus, Being and Nothingness (1943), which I wrote about in 50 Philosophy Classics, that has stood the test of time.

Being and Nothingness caught the mood of post-war France in which all the old certainties had crumbled away. If France’s existing value system had got it into such a mess in the War, Sartre wondered, was it worth anything?

Perhaps, out of the wreck of institutions, society, and religion could rise something new: the free-thinking individual.

In true French intellectual fashion Sartre’s prose can be impenetrable. You have to read between the lines to obtain his full message.

Yet I believe that, rather than being a textbook of postwar nihilism, Being and Nothingness contains a philosophy of freedom and success that’s still inspiring.

Let’s look closer at what, in a strange way, was the motivational book of its time, inspiring the Beatnik movement and the hippies after them.

We are “nothing”… so we can be anything

At the start of the book Sartre discusses consciousness, and divides the world into two:

1) Things that have consciousness of self i.e. human beings

2) Things that do not i.e. the objects around us that make up the world

Sartre offers the paradox that although humans possess “being” in its truest or highest sense i.e. consciousness of self, at the same time we have no essential “essence.”

When we analyze our own being, what we find at the heart of it is … nothing.

Yet this nothingness is something great. It means that we are totally free to create the self or the life we want.

We are free in a negative way, because there is nothing to stop us being free.

No accidents, no excuses

Along with this existential freedom comes responsibility.

Not only are we responsible for what we do, we are responsible for our world.

How so?

We each live out a certain project with our lives, so whatever seems to ‘happen’ to us must be accepted as part of the project.

Sartre goes as far as saying that “there are no accidents in life”.

His example is being called up to fight in a war:

I may think of the war as an external thing that comes from outside and suddenly takes over ‘my’ life, taking me away from what I ‘really want to do’ (pursue a career, have a family etc).

I may wish I lived in another time, but the fact is I am part of the epoch which led to war. My life is an expression of the era I live in, so to wish for some other life is a meaningless, illogical fantasy. “Thus, I am this war...”

Yes, I could get out of it by killing myself or deserting, but for one reason or another (cowardice, inertia, or not wanting to let down a family or a community), I stay in the war. In doing so, “For lack of getting out of it, I have chosen it.”

Sartre served as a meteorologist in World War II. He became a prisoner of war and was later discharged from military service due to ill health.

He believed it was an act of mental freedom to make the war his war. He was successful to the extent that he exercised that freedom.

Success is not important to freedom

People mistakenly try to say that what they are doing is all important. But one of Sartre’s most intriguing remarks is, “Success is not important to freedom”.

You don’t have to attain what you wished to be free, you just have to be free to make a choice in the first place. Claiming that freedom and exercising it is in itself successful, more than any outcome or result.

Living as if our actions are all-important, or trying to align ourselves with some universal moral value system, is a kind of “bad faith” (mauvaise foi). Only by truly choosing for ourselves what we will be every minute, while not taking ourselves too seriously, do we have a successful life.

Sartre: “Man is what he is not and is not what he is.”

He means that we can’t escape our “facticity” – the concrete facts of our existence like our sex, nationality, class, and race. All of these provide a “coefficient of adversity” which makes any kind of achievement an uphill battle.

And yet, we are never simply the sum of our facticity. Despite all the limiting factors of our existence, we are freer than we imagine.

The problem, Sartre says, is that we shrink back from doing totally new things, things out of character, because we value consistency.

Yet consistency, or “character”, is a form of security. It stops us from fashioning a new, free self.

How “bad faith” holds us back from genuine success

Sartre writes about the lie of consciousness where we try not to look too closely at our life for fear of what we might find. This is a flight from freedom, because, “it is from myself that I am hiding the truth.”

Sigmund Freud believed that people’s choices and actions are constantly hijacked by their unconscious minds, but when Sartre sat down to read Freud’s cases for himself, he found that the people on the Viennese doctor’s couch were simply examples of pathological bad faith, or lying to themselves.

It is not easy to become sincere or authentic, Sartre says - it does not happen naturally. It must be a conscious act, in which a person’s new candor “ceases to be his ideal and becomes instead his being”.

This authenticity is the meaning of life. The absence of it is the definition of failure.

My own theory of success, published a few weeks ago, says the same: the opposite of success is not failure, it is living a lie.

Sartre on love and successful relationships

Sartre’s views on this are worth a quick detour, since success in love is surely an important part of success.

We our lover to see us as special, as something limitlessness: “I must no longer be seen on the ground of the world as a ‘this’ among other ‘thises’, but the world must be revealed in terms of me.”

Relationships are a perpetual dance between lovers wanting to allow each other’s freedom - and wanting to see each other as an object. Without the other being free, they are not attractive, yet if they are in not some way an object, we cannot “have” them.

We try to make others dependent on us emotionally or materially. Yet we can never possess their consciousness. “If Tristan and Isolde [the mythical love pair] fall madly in love because of a love potion”, Sartre writes, “they are less interesting” – because a potion would cut out their consciousness.

Sartre argues that it is only in recognizing the other as free that we can be said to possess them in any way. Yet ironically, reducing ourselves to an object to be used by the other (e.g. in sex), but in a voluntary way, is in a strange way the height of being human, since it is a kind of giving that goes against the very human wish to be free.

Consistent with their refutation of all bourgeois or middle-class values, Sartre and de Beauvoir never married or had children, but their union of minds made them one of the great couples of the twentieth century. They lived in apartments within a stone’s throw and would spend several hours a day together; they admitted that it was difficult to know which ideas in their writing originated with one or the other.

Sartre’s and de Beauvoir’s devotion to each other survived affairs on both sides, and even the sharing of lovers of both sexes. Why? Because in their minds success equated to freedom, and they freely gave each other their conscious minds.

Conclusion - Sartre’s recipe for success

For a person who said that appreciating one’s freedom and state of being was more important than “bourgeois” achievements, Sartre nevertheless set out to be a cultural giant of his times like a Voltaire or Balzac. In that he was hugely successful.

Sartre was a self-admitted “book-making machine”. He wrote classic novels (Nausea, 1938); short stories (The Wall, 1939); plays (No Exit, 1944); essays and criticism (Anti-Semite and Jew, 1944, What is Literature?, 1948); biography (Saint Genet, Comedian and Martyr, 1952); philosophy (Being and Nothingness, 1943); and autobiography (Words, 1964), plus hundreds of influential articles.

He traveled widely, visiting Cuba to meet Fidel Castro and Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara, and to China and Brazil. In 1964 he refused the Nobel Prize for literature, saying it would compromise him. His Marxism aside, he was assuredly “successful” by any hard measure in his time, and crucially he continues to be read and studied.

Sartre said that “Success is not important to freedom.” But could it be said that he left us with a recipe for success?

I believe yes.

Apart from the broader ethic of individual freedom, Sartre’s recipe for life is to “insert my action into the network of determinism.”

He means we must accept the milieu into which we have been born, yet be willing to transcend it by pursuing a life that is conscious, intentional, and original. Being and Nothingness is a warning not to let the apparent facts of our existence (our facticity) dictate its style or nature. We must be self-made. (I incidentally argued the same in my recent critique of Malcolm Gladwell’s Outliers).

Sartre lived out this philosophy. The death of his father when he was quite young meant that there was no pressure to model himself on his parent, and he felt free to invent himself as whatever person he wished. That he did - with alacrity.

Insisting on mental freedom can be a psychological burden, but if we do not embrace it we slip into bad faith, or living a lie. If Sartre is right that there is “nothing” at the very heart of a person, this should compel us to create what we think is the best version of ourselves.

Success, in Sartre’s philosophy, always comes back to freedom and truth, or authenticity. This chimes with my own definition: success is truth.

Kind regards,

Tom Butler-Bowdon

What do you think? Add your Comments below.

If reading this via email, click into the post to Comment.

Please Like and Share this if you found it interesting!

Thanks - Tom

Author of the 50 Classics series (click to find out more)

Editor of the Capstone Classics (click on image for more info)

Find me:

Explore my website Butler-Bowdon.com with free book commentaries and interviews

NEW: Chat with me or ask a question (AI Tom in Beta)

Connect & follow:

Twitter/X - follow

LinkedIn - connect

Superb article. I’m drawn to facticity and Being, a la Heidegger but I find him hard to understand. Maybe I’ll start here instead.