In the last post I looked at what academic psychology has found to be the trait most linked to success: Conscientiousness.

However, conscientiousness is, by nature, hard work.

I promised to reveal another outlook or strategy that can make you relax a little while increasing your chances of remarkable success.

This mental ‘hack’ costs you nothing, involves little mental energy, and is even fun.

It is not a Big 5 psychology trait.

Indeed, it is a bit ‘woo woo’ so won’t get studied by psychologists.

What is it?

Let’s begin.

An Early Feeling

In his book Unreasonable Success (2020), investor and author Richard Koch looked into the life stories of 20 people, from Da Vinci to Disney, Keynes to Thatcher, Mandela to Bezos, Madonna to Helena Rubinstein.

He believed he had identified the most important trait of the ultra-successful.

This trait is so important because it’s often all a person has at the start of their lives or career.

At the start they have no idea how to become “someone”. But unlike most people, they have a sense that they will, one way or another, be remarkable.

As Richard Koch puts it:

“Self-belief can start - as it did in about half the people I studied - with a vague general belief in their ‘star’ or destiny.”

Many had this feeling early in life, when there was no rational reason for it.

According to biographer Andrew Roberts, Winston Churchill told a friend that he would come to London’s rescue when it was attacked:

“In the high position I shall occupy, it will fall to me to save the capital.”

Churchill was 16 at the time.

Of course, Churchill had illustrious ancestry: he was related to the Duke of Marlborough who had won the battle of Blenheim and been lavished with honors by the British state. Churchill’s father Lord Randolph Churchill was part of the Tory establishment. As Koch wryly notes, “There is nothing more conducive to self-belief than belonging to a homogenous elite”.

And yet, of the 20 ‘greats’ Koch looked at, he found that for 17 of them, “heritage and background [were] irrelevant to their self-belief.”

This deep self-belief came to them in an apparently natural and random way.

It manifested as “a vague but deep sense of being special”.

Koch calls this ‘self-belief’, which is a rather prosaic term from psychology.

There is a much older phrase that I believe better expresses the glory of what we are talking about.

One that invokes the Gods. One which has become taboo:

A Sense of Destiny

In an Age of Equality, it suggests forbidden specialness and conceit, so is not allowed.

In an Age of Psychology, it sounds too metaphysical, so is ignored.

Sit down with a careers counselor or HR consultant and they will ask you about your ‘career trajectory’.

But talk about destiny and you’re likely to get strange looks. The same goes for using the word ‘calling’.

But mission, destiny, and calling have each been around a very long time.

Think about Mother Teresa who, while on a train from Kolkata to Darjeeling in 1946, had a ‘call within a call’ (she was already a nun) to leave her convent and devote the rest of her life to helping the poorest of the poor. Her superiors were perplexed, but she just knew.

Do not confuse a special mission or feeling of destiny with selfishness.

A sense of destiny is about accomplishing a great thing that - although only you can do it - will benefit many.

The definition of ‘greatness’ is large positive impact on the world.

So don’t be ashamed of it.

How exceptionalism begins

Someone who had a sense of specialness from early on, yet whose background provided zero reason for it, is Bob Dylan.

Born Robert Allen Zimmerman, he had an unremarkable upbringing in small town Minnesota, with unremarkable parents. But his exposure to the music of his time changed everything.

He said in a 2004 interview:

"You're born, you know, the wrong names, wrong parents. I mean, that happens. You call yourself what you want to call yourself. This is the land of the free."

Critics argued that it was his world view and persona, more than his singing or musical ability, that made him famous.

Dylan himself admitted in Chronicles: “There were a lot of better singers and better musicians around these places, but there wasn’t anyone close in nature to what I was doing.”

Where does this sense of exceptionalism come from?

Richard Koch says it “can arise from defiant vulnerability or isolation in childhood, when the self is thrown back on itself and creates an imaginary future to compensate for a barren present.”

That sounds a bit Freudian, but it’s true that without role models in his immediate milieu, Dylan had to create an imaginary lineage to someone great.

He did this with Woody Guthrie. Dylan knew 200 of Guthrie’s songs by heart and once tracked the artist down to a hospital where he was laid up, just to sit at the feet of the master.

Even so, many great people had no particular mentor or role model. Einstein, for instance, came near the bottom of his class at Zurich Polytechnic, and worked alone. Yet in an age of hierarchy and deference, he had no qualms about exchanging letters with renowned physicists, seeing himself as at least their equal.

“Despite lack of academic success, the young Einstein had supreme faith in his own intuitive judgement,” Koch notes.

In an earlier post on Malcom Gladwell’s theory of success I mentioned the story of Coco Chanel.

Both of Chanel’s parents died when she was young, and her only 'mentors’, if you can call them that, were nuns at her orphanage who taught her to sew. She had male lovers who were useful to her rise, but she was no ‘Fair Lady’ being sculpted by them. Rather, they were useful to her in getting where she wanted to be.

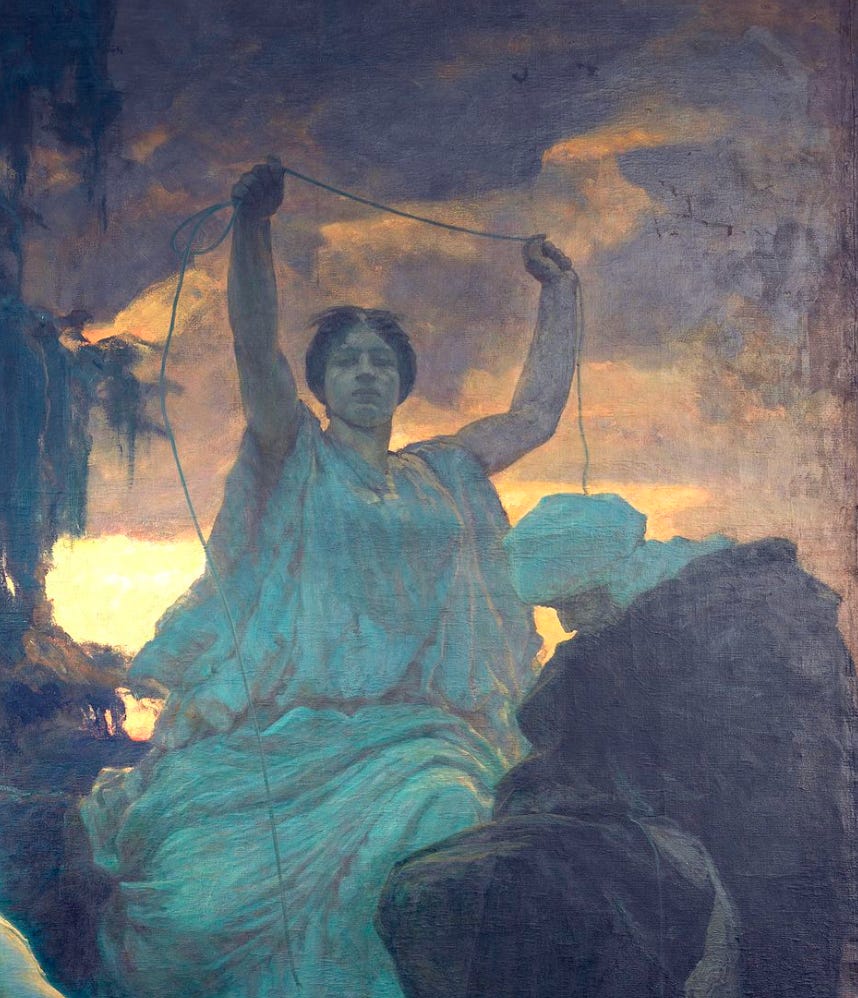

Here’s Marius Borgeaud’s portrait of Chanel, at a time she was breaking out as an important couturier. She is in the latest fashion, but that is almost irrelevant. Look at the steely, inner gaze. It’s about her. What she is, what she is becoming.

The sense of destiny that some people feel gives them a lordly sense of relaxed superiority.

Others sense that, and wish to get behind them.

The question is - given the potentially huge payoffs - can a ‘sense of destiny’ be manufactured?

Can you make it part of who you are even if, at this moment, your self-belief is not strong?

How to create a sense of destiny

In his book, Koch provides three useful strategies:

1) Seek out a “transformational experience” where you can grow quickly e.g. a job or a position that seems beyond your ability, but offers a great opportunity for self-discovery, increase in skills, and the chance to shine. In other words, put yourself on a path to greatness.

2) Attract praise. “Self-belief is hard if you get little applause. Today children get too much and adults too little.” Praise is important because it can confirm what self-belief we do have. Get a mentor who is happy to hype you up to others.

3) Narrow your focus until what you are doing is unique. Self-belief must become attached to achieving an unusual or very specific goal. Why? Because if it’s unusual, all the more likely that only YOU can achieve it.

Of his subjects, Koch says:

“As with everyone who achieves marked success, they come to believe either that they can do specific things better than their rivals, or that they can do something that nobody else has thought of doing.”

When this thought is internalized, it slowly transforms into a sense of destiny.

But this is key:

It doesn't matter if, at the start, your belief is totally irrational.

Faith is not rational.

Yet the person who ‘knows’ before the truth is made manifest has a huge advantage over pure rationalists, skeptics, and naysayers.

The Golden Thread

Writing of Napoleon and Alexander In his 1948 classic The Magic of Believing (which I write about in 50 Success Classics), Claude Bristol says:

“They became supermen because they had supernormal beliefs”.

Napoleon was given a star sapphire when he was a boy, accompanied by the prophecy that it would bring him good fortune and make him Emperor of France. Napoleon accepted this as fact, and therefore to him at least, his rise was inevitable.

The subconscious mind operates via imagery, Bristol points out, so it is vital that we feed it very clear mental pictures of what we desire. It can then go to work in ‘living up to’ the image placed before it. It will give us intuitions about what to do, where to go, whom to meet.

As a city journalist who covered the Religion beat, Bristol learned the “golden thread” which runs through all religions and esoteric teachings: that belief itself has amazing powers.

But how does this work?

It was not impossible, said the astronomer Sir Arthur Eddington, that the physical laws of the universe could be to some extent made subject to human thought. Quantum physics does not rule this out either.

Carl Jung’s idea of the 'collective unconscious' says that our mind is connected to all other minds. Even without saying anything out loud, the force of our belief acts like a broadcast to other people and even inanimate objects. The more powerful this 'broadcast', the more likely others will pick it up and react accordingly.

Bristol's explanation is that a person with a strong belief will exist at a certain ‘vibration’ that seeks its like in the form of matter. Depending on the quality and intensity of your belief, ‘hidden hands’ will reach out to help. This assistance comes not from work as such, but from the clarity of your vision.

‘Charisma’ is simply the power field of a person who has this clarity. Others feel it, even before knowing why.

Final word

I have the greatest respect for psychology’s ‘Big 5’ traits of personality that are meant to have such an influence on our lives.

But ultimately they are less important than a mental hack that many of the greatest figures in history knew about and used.

Cultivating a sense of destiny costs you nothing, is inspiring, and can shape your future in ways you can’t even imagine.

Has a ‘feeling’ or epiphany ever come to you about your future?

Don’t dismiss it. Indulge it.

Beyond obvious things like skills, education, and hard work, it’s this strange, unquantifiable thing that may set you apart from your peers.

What is it, exactly?

It’s your future or higher self trying to tell you why you are here.

Don’t ignore it or downplay it.

Kind regards,

Tom

What do you think? Add your Comments below.

If reading this via email, click into the post to Comment.

Tom Butler-Bowdon

Author of the 50 Classics series (click to find out more)

Editor of the Capstone Classics (click on image for more info)

Find me:

Explore my website Butler-Bowdon.com with free book commentaries and interviews

NEW: AI TOM

I have a new AI alter ego

“AI Tom” is trained on my all books and content

Chat with Tom or ask a question!

Gain knowledge or ask for success tips

Text or audio

Connect & follow:

Twitter/X - follow

LinkedIn - connect

I would be inclined to agree with this. It's funny how many famous people, when asked, say they always knew they'd reach the position they've now accomplished. A smaller example is Paul McKenna. I remember reading a Sunday Times article where he said he always KNEW he was going to be famous. As a kid, he thought this meant being the next James Bond but he found his niche as a stage hypnotist.

Interesting Tom - thanks! It gets me asking further questions about whether these past exceptional self-believers had exceptional belief thrust upon them or needed it through defiance etc. If they wished to have exceptional belief, then was there a particular reason for this wish to be stronger than in most others?