Unhurried Time & the Real Source of Money + FREE e-book

Seneca, India, Rockefeller, Ponder

Hello,

In his essay On The Shortness of Life, Stoic philosopher Seneca observed how people lust after success and power.

Yet when they finally achieve some high position all they can think about is when they can leave it and free themselves from the pressure and difficulties of the job.

Some daydream of their next vacation, others fantasize about a time when they will not be so busy and can live like normal people.

In A Promised Land, Barack Obama reveals that at the height of his presidency he was having dreams about sauntering to a local park, sitting on a bench and watching the world go by.

He’d wake up and remember he was leader of the free world.

Last year, when I was up to my neck in work, I also started having fantasies about doing nothing: pottering around the house, visiting a nearby village for a coffee, reading the papers with a free afternoon stretching ahead.

It remained a fantasy, but I did stick religiously to a weekend “sabbatical” involving no work, no email, and no social media between 6pm Friday and 8am Sunday. It kept my sanity and allowed time for reflection.

Even so, it wasn’t enough. I started longing for a genuine sabbatical, like 2-3 months.

So at the end of 2023 I finished my 3-year stint with Memo’d, the knowledge app, and began a long holiday in Australia and the Subcontinent. It’s amazing how quickly you adjust to not working, and I’m not sure I had any great epiphanies. It was just nice spending unhurried time with family, meeting up with friends, enjoying the sun, surf and nature (in Sydney, Gold Coast and Byron Bay), and having a bit of an adventure (in India, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka).

My “two month” sabbatical seems to be stretching well into 2024. There are projects I’m working on, but it’s only a few hours a day. There’s time for swimming, gym, meditation, socializing, travel, investing, politics, and reading.

Seneca noted how many people he knew (including very rich people) were not in control of their time. They had to constantly manage people, money, legal matters, and property. Seneca himself, thanks to his years as tutor, adviser, and power-behind-the-throne to a young Emperor Nero, became incredibly rich, with houses and estates scattered around the Italian peninsula.

As a young man Seneca was very ambitious, and must have been gratified to become, in order, a respected senator and lawyer, literary celebrity, Consul (the highest position in the Roman empire bar the emperor), and billionaire (in today’s money).

Yet his essays and letters mention these roles surprisingly little. Instead he wants to discuss Stoic virtue and how a philosopher should live.

In On The Shortness of Life, he warns:

“When you see a man often wear the purple robes of office, and hear his name often repeated in the forum, do not envy him; he gains these things by losing so much of his life. Men throw away all their years in order to have one year named after them as consul.”

A few years later he was Consul, with everything that brought… including the stress of having to defend an increasingly mad Nero.

Seneca slowly extricated himself from the heart of Roman power and spent more time writing. In one year alone (AD 62) he penned On Benefits, Moral Letters, On Providence, and Natural Questions.

More than most, he knew that the greatest luxury, one you cannot put a price on, is unhurried time.

A vagrant has plenty of time, but no meaningful work.

A CEO finds their work meaningful, but they have no time.

If you can achieve unhurried time + meaningful work, consider yourself one of the fortunate few.

Where does money come from?

A funny thing happened in India.

In an auto-rickshaw on a busy Guwahati street, I was holding my wallet when the driver turned a sharp corner. I slightly lost control of the wallet while leaning out the window. But fortunately I never let go of it.

About an hour later, when I had to pay for a visa, I realized my debit card was missing. It must have fallen out of the wallet!

It was weird because there were a lot of cards (driver’s licence, gym card, library card, loyalty cards, etc), but the one I really needed while traveling - my bank debit card, was the one that that flew onto the road, never to be seen again.

I stayed calm and tried to be philosophical. Maybe the incident was trying to tell me something.

Via the 50 Classics series I’ve written about a lot of books that fall into the genre of “prosperity consciousness” - from Charles Fillmore’s Prosperity (1912) and Genevieve Behrend’s Your Invisible Power (1921), to Catherine Ponder’s Open Your Mind to Prosperity (1982) and Esther & Jerry Hicks’ Ask And It Is Given (2004).

What I absorbed from these writings is that “God is the source of your supply, not persons or conditions”.

You can replace “God” with “The Universe” or “Infinite Intelligence” or “Mind”, depending on your metaphysical beliefs, but the principle is the same.

Even if you’re an atheist materialist, you’ll admit that believing that your job or the economy or your bank account is the source of your prosperity is like believing that food comes from supermarkets. It’s where you get it, but it’s not the source.

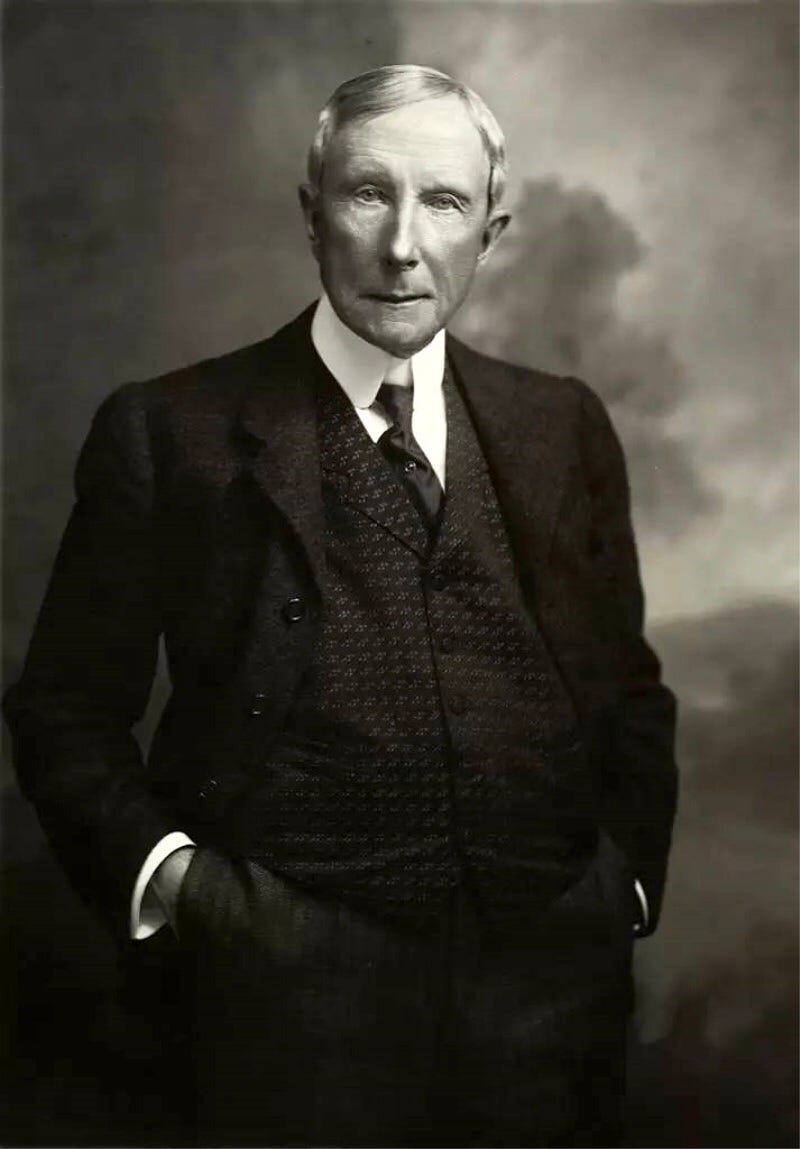

For a long time, John D. Rockefeller was the richest person in the world. Many believed him to be rapacious and corrupt, but when he started giving away billions to end infectious diseases and build new universities, the world seemed to forget his sins.

“God gave me my money,” Rockefeller would say. And he meant it. As a boy he’d been encouraged by his strict Baptist mother to donate a percentage of whatever he earned, and he recorded his giving in a diary (which still exists in the Rockefeller archives). He would follow John Wesley’s advice (from the sermon, The Use of Money) to “earn all you can, save all you can, give all you can.”

Rockefeller’s tithing was not 10% (the customary amount), more like 2-7%. But on the vast scale of his adult earnings, it was a lot.

Rockefeller deeply understood the nature of money; that it is circular. It flows when shared, and by giving away a certain portion of what you earn, you affirm this universal law. One effect is that you develop a relaxed knowledge that you in turn are a beneficiary of this flow.

Inspired by the prosperity writers, some years ago I started methodical giving even when it made no sense financially. I was starting out as an author, and in debt. But I saw it as an experiment to test the ideas of supply and circularity. Were they really universal laws?

Sometimes the effects were immediate. I would send off a donation cheque for $100, and the next day get notified of a bonus publisher payment I wasn’t expecting… for $100. But usually, the effects were on a longer timeframe: whatever I gave, in time it was easily outstripped by rises in annual earnings, and often from sources I’d not expected.

I discovered another law: that if you want something for yourself, the best way to get it is to give it to others. When I started to frame giving in terms of the thought, “I want them to have enough for their needs”, I found myself having more than enough for my own, and to have to worry less and less about money.

This law of “if you want something, give it away first” I first learned about in The Diamond Cutter, by Geshe Michael Roach. Most of the prosperity genre is Western, but this book’s Buddhist understanding of the connection between mind and money went against everything I’d read in the conventional success genre. I’m still thinking about it (and trying to apply it).

I also found that if you start to affirm universal abundance at every chance, opportunities arise that you never expected, or you “see” opportunities that others do not. This dynamic, which arises out of the concept of “emptiness”, is at the heart of Roach’s book.

“I have little to give”, you say.

The amount doesn’t matter. It’s about having an intention and acting on it. It doesn’t even need to be financial. You can make wishes for the prosperity of your friends, or people you don’t know personally who look like they need it. The wish is not that they suddenly get some windfall, but that their conditions change such that a path to prosperity opens up for them.

Chances are if you are loved or admired, you have been borne upwards by the good wishes of others. These mental acts would not have become part of our culture if they had no effect.

Back to my lost debit card. I’m usually pretty careful about possessions, but the strange way it happened - I literally threw my card out the window, as if I didn’t need it - I took as a reminder that a thing (a person, a job, a card) is never the source of my prosperity.

My brother, who I was traveling with, kindly helped me out with rupees in the short term, and I remembered I had a credit card I could withdraw cash with. So two other “sources” immediately appeared.

As the trip went on I tried to be more generous. At our beach lodgings in Sri Lanka, the proprietor expected us to bargain her down on the accommodation, but my brother insisted we pay the full price. She later told us she had given some of our money to her local Buddhist temple, an act that would now bring us “merit”.

* * *

Time is an arrow; it never goes backwards.

Money is a boomerang.

Whatever is given with good intention and for the benefit of others, always comes back… usually in greater amounts.

Films like The Secret and books like Think and Grow Rich can seem a bit cheesy, but the basic laws they talk about are true. I have made myself a guinea pig for this stuff, and can vouch for it.

* * *

I’d like to offer you a FREE 45-page e-book, Nine Prosperity Classics, adapted from my full-length book, 50 Prosperity Classics.

Nine Prosperity Classics includes summaries of some significant writings in this field, including Behrend, Fillmore, Byrne, Hill and more - and my thoughts on them.

To receive it, send me an email here and put “Prosperity” in the title bar.

If there’s a delay in getting back it’s because I respond personally, no automation.

By the way there’s no catches, it’s just something I thought you may find helpful or interesting.

Would love to hear your own experience of this stuff.

Thank you.

Kind regards,

Tom

Tom Butler-Bowdon

Author of the 50 Classics series

Editor of the Capstone Classics

Find me

I may have stumbled upon this random article at exactly the right time

Tom- I like this boomerang analogy, especially as it pertains to wealth and meaning. Hope you're well this week. Cheers, -Thalia