Hello,

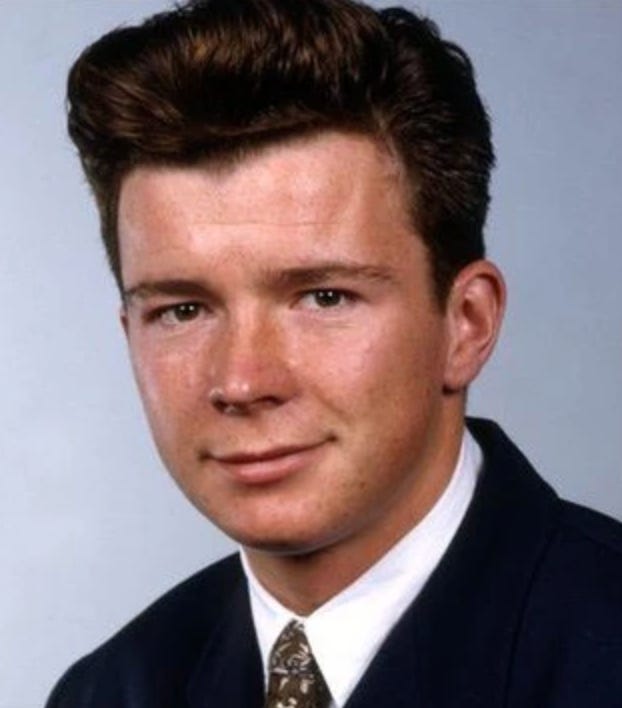

Rick Astley, singer of Never Gonna Give You Up (1.5 billion views on YouTube) has written an autobiography.

The Financial Times’ Emma Jacobs discussed the book, Never, in an article, “Never gonna admit we’re lucky” (Nov. 9, 2024).

Astley paints himself as a guy who happened to be in the right place at the right time. Luck was half his story:

“You can have drive and ambition and talent, but there’s a huge amount of luck involved too: you know, someone wrote a three-and-a-half minute pop song in 1987, and my life completely changed as a result of that. It’s ridiculous, really.” - Rick Astley

Alluding to ‘luck’ is a way for modest people to explain their success without seeming strategic, calculating or rapacious.

They hide their ambition and downplay success as if it’s just something that “just happened to them”.

Socially, it’s much safer to say one’s career “just happened” or “I never had a plan”. It’s also in the British character to downplay one’s agency, and Rick Astley is considered a ‘nice guy’ of British pop.

Whether you like Astley’s music or not (I love Never Gonna Give You Up as much as anyone) is not the point of this post.

Rather, I want to contest the view of success that is expressed in the Jacobs article and Astley’s book.

Let’s find out if it’s actually true.

Ambition 9% of success?

In her article, Emma Jacobs starts by saying that, as she’s got older, she appreciates “the seemingly arbitrary nature of success”:

“When I look back at peers who have done well in their careers, for some it was always inevitable: they hustled harder, or their talents was inarguable. But for others it looks like chance.”

Jacobs draws on the work of organizational psychologist Tomas Chamorro-Premuzik to support her thesis.

Chamorro-Premuzic argues (“Talent, Effort, or Luck: Which Matters More For Career Success?”, Forbes, Sept 2021) that successful people overestimate the role of talent and drive, and underestimate blind chance and randomness, including fortunate ‘tailwinds’ such as the time in which you live (echoing Malcolm Gladwell’s theory of success).

Because our environmental advantages are given to us, we tend to discount them. At the same time, we exaggerate how much an achievement is really our own.

Chamorro suggests that “no more than 9% of a person’s success can typically be attributed to their ambition, drive, or motivation.” And the combination of ambition/drive + work + talent make up no more than 40% of a person’s success. The rest is ‘luck’:

“[It] is rather obvious that factors not associated with either talent or effort make some people “luckier” than others: privilege, where you are born, who you are born to, etc. These universal drivers of success are not the result of people’s merit… but the lottery of life. Gender, race, nationality, and socioeconomic status at birth all amplify or handicap people’s potential, and for reasons unrelated to their own skills, decisions, or motivation. The more privileged you are, the less talent and effort you will need to attain high levels of success, and vice-versa. For example, being born in Singapore, Canada, or Denmark is generally advantageous to being born in Afghanistan, the C.A.R., or Haiti.”

Chamorro mentions Napoleon Bonaparte’s success formula:

“Luck favors the prepared man”.

He argues that many of the things that create ‘preparedness’ have nothing to do with merit: good genes, attractiveness, family wealth, parents’ education, gender, ethnicity etc.

Fair points, but drive/ambition accounting for only 9% of success?

Let’s look at our Exhibit A, Rick Astley.

Pre-success Rick

I wrote in Never Too Late To Be Great: The Power of Thinking Long that what happens before a person is famous is often more interesting and instructive than what happened after.

It turns out that Astley was much, much more driven to succeed than his peers.

Born in 1966, his childhood and teen years were in an unremarkable town in the north of England, Newton-le-Willows. Family life was not particularly easy or stable. His father ran a garden centre, was known as the local eccentric and had an explosive temper. He threw Rick’s mother out of the family home on suspicion of an affair. At school, Rick was known as the boy who “lived in a Portakabin in a field”. No-one he knew went to university. It was expected that he’d join his dad working in the garden centre.

Rick reacted to these circumstances by being determined that his adult life be one of “stability, freedom, and prosperity”.

He was in a couple of bands in his late teen years, and was always the driving force.

Talking of his second group, FBI, he says:

“I was either conceited or stupid enough genuinely to believe that we were going to make it. I really had a fire in me. I thought we had a tiny window of opportunity to make it happen… I wasn’t sure the others felt that way…there were times when I literally had to get them out of bed to practise.”

When his brother Mike’s idea of a bright future was “signing on the dole and waiting to see if anything came up”, Rick was telling his friends that he was “going to be as famous as David Bowie”.

Astley’s mother “was an amazing pianist… who could sight read classical music… and could simply pick up any tune.” He grew up listening to older siblings play Motown and Northern Soul, along with Pink Floyd, Queen, the Beatles, Genesis, and Rick Wakeman. He was obsessed with The Smiths, The Police, AC/DC, and learned the drums and other instruments entirely on his own.

Astley knew he had a talent (“when I sang, it attracted attention”). People did not expect the voice that came out of smallish English guy to sound Black, soulful, and strong.

So he was clearly more ambitious than his peers, and had some talent.

Yet he says that he “never had a plan”.

Astley’s ‘lucky’ break

In 1985, the music producer Pete Waterman came to see FBI play. Impressed, Waterman suggested Astley come down to London and spend time with him in his studios.

Astley felt loyal to FBI, and Waterman was not then a big name. On the other hand, how many opportunities like this might come along? Intuition said GO.

Astley signed a contract, but spent the next year making tea for singers and bands who passed through the studios of Stock-Aitken-Waterman. But he didn’t mind; he was getting priceless experience of the music industry and meeting artists.

Eventually, Waterman and his team developed a song for Astley to sing and record. Astley loved it and pushed for it to become a single.

Released in 1987, Never Gonna Give You Up would go to No. 1 in the UK, then in the USA, and around the world. It was followed up with other hits and bestselling albums.

In the 90s, Astley had a long career lull when he raised his daughter. He thought people had forgotten him, and he was happy to tinker away in his home recording studio.

Then the resurrection: In the mid-2010s, 80s music was ‘in’ again, and his new album 50, in 2016, became a surprise hit. He also benefited from the ‘Rickrolling’ meme, where people tricked friends into believing they were clicking on a serious link, only to find themselves on the YouTube page for Never Gonna Give You Up.

In 2023, Astley was asked to be a headline act at Glastonbury alongside Guns n’ Roses and Elton John. Now good friends with Dave Grohl and Foofighters, he was finally cool.

Truth revealed in time

In his bestseller Thinking, Fast and Slow, psychologist Daniel Kahneman provides this formula:

Success = talent + luck

Great success = a little more talent + a lot of luck

He also applies it to companies:

“The comparison of firms that have been more or less successful is to a significant extent a comparison between firms that have been more or less lucky.”

Kahneman’s research about thinking biases is mildly interesting, but overall I got little from Thinking, Fast and Slow.

And I 100% disagree with his success formula.

The contention that successful firms are merely the most lucky ones is absurd. Was the rise of Amazon, Microsoft, Apple, Berkshire Hathaway… random or ‘lucky’?

Part of the issue is that people such as Kahneman and Malcolm Gladwell have a shallow interpretation of success. For them, it’s when a person or company is in the limelight or seems to be winning.

My definition of success - Truth revealed in time - means that the weighing action of time allows us to get a better idea of who or what is genuinely successful beyond today’s often very mistaken opinion.

In the short term, it’s easy to come to the view that someone’s success is the result of fortunate circumstances.

In the long term, it’s impossible to do so, because the more time elapses, the clearer it gets that success did not just ‘happen’ to an entity, it was built.

Here’s an alternative formula:

Success = circumstances + talent + work + prior impressions & intentions

Great success = as above, on a larger scale

An argument can be made that fortunate birth and circumstances account for perhaps 70-80% of a person’s success up to the age of 20.

But as a person gets older, this arithmetic falls apart.

The older we get, the less ‘luck’ is involved in our success, and the more it is the outcome of earlier impressions and causes in the form of generosity, imagination, foresight, and work.

Business books like Good to Great, and motivational books like The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F***, fail to lead to business or personal success for their readers, because how or when you become successful can only come from the fruition of earlier causes and impressions (let’s call it karma) unique to you. It’s simple cause and effect.

I’m reminded of Ray Kroc:

“People have marveled at the fact that I didn’t start McDonald’s until I was 52 years old, and then I became a success overnight. But I was just like a lot of show business personalities who work away quietly at their craft for years, and then, suddenly, they get the right break and make it big. I was an overnight success all right, but 30 years is a long, long night.”

What Jacobs/Astley/Chamorro/Gladwell/Kahneman call ‘luck’ is for the most part the outcome of previous actions and impressions.

We are beings that exist in time and space, and so it naturally takes time for our mental impressions to take form in the world. A thought becomes a word, a word leads to an action, and so on.

Emma Jacobs said that age had made her appreciate “the seemingly arbitrary nature of success”.

I say the opposite: the longer a person is around, the less arbitrary their success becomes.

Success isn’t random

Dr Richard Wiseman is professor of the public understanding of psychology at the University of Hertfordshire, and author of The Luck Factor: The Scientific Study of the Lucky Mind.

Wiseman spent no less than 10 years studying luck, and his conclusions run counter to the Jacobs/Astley/Chamorro/Gladwell/Kahneman view.

Wiseman’s finding in a nutshell?

‘Luck’ is the outcome of measurable habits:

“[Luck] is not a magical ability or the result of random chance. Nor are people born lucky or unlucky. Instead, although lucky and unlucky people have almost no insight into the real causes of their good and bad luck, their thoughts and behaviour are responsible for much of their fortune.” (Wiseman R. 2003 p. 2)

Wiseman identifies four behaviors that people use to create good fortune in their lives:

Maximize chance opportunities. Lucky people are skilled at creating, noticing and acting upon chance opportunities.

Listen to lucky hunches. Lucky people make effective decisions by listening to their intuition and gut feelings.

Expect good fortune. Lucky people are certain that the future is going to be full of good fortune.

Turn bad luck to good. Lucky people employ various psychological techniques to cope with, and often even thrive upon, the ill fortune that comes their way.

Whether consciously or not, Astley employed all four of these.

He could have shrunk back from opportunity and stayed in Newton-le-Willows. Instead he left behind everthing he knew. He hyperbolically told people he would be “as famous as David Bowie”. And he used the trauma of his upbringing as a reverse motivation to achieve stability and prosperity.

In short, Astley put himself in the position he needed for ‘luck’ and ‘chance’ to work for him - just as Wiseman says successful people act.

Astley took the same strategy in his private life.

When Rick met his longstanding wife Lena Bausager, he was in a relationship with Debbie, a local girl he’d been with since his teens. The relationship was not coping under the strain of Astley’s fame and constant travel. At the same time, Astley didn’t know how to end it. If nothing happened, marriage and kids would soon come.

Opportunities narrowing, Astley jumped on a plane to Denmark to join the surprised Lena, then a music industry person who had been responsible for organizing an Astley tour of Denmark.

In his book, Astley rues the way he ended things with Debbie (he just left her a note at the house they had bought). But he does not regret taking quick, decisive action to woo Lena, the love of his life.

Luck is a fiction

Jacobs ends her Financial Times article by repeating something Astley had told over over the phone:

“The difference between success and failure is a knife edge.”

100% it’s a knife edge, but not because of ‘luck’ or blind chance. As any Olympic gold medallist will tell you, where the knife falls is the result of thousands of previous behaviors and choices.

The favorite, your nemesis, pulls out of the final due to a hamstring injury. You win. What incredible luck! No, part of your conditioning was preventative training which made such injuries much less likely. You were prepared. You were on the starting line.

I find it fascinating that Wiseman says:

“lucky and unlucky people have almost no insight into the real causes of their good and bad luck”

And yet:

“their thoughts and behaviour are responsible for much of their fortune.”

Is it possible that figures such as Napoleon and Churchill became remarkable because they did have insight into the causes of their ‘luck’?

Both men knew, for example, that having a ‘sense of destiny’, made all the difference.

The really great people know that luck is a fiction.

Even the things they do not control, such as the circumstances of their birth, can be used to fashion the self and the world they desire.

Fortuity: Success from apparent randomness

“The Psychology of Chance Encounters and Life Paths” is an article that Albert Bandura published in 1982 in American Psychologist.

Bandura (see 50 Psychology Classics) argues that “some of the most important determinants of life paths occur through the most trivial of circumstances.”

Yet these trivial or apparently random circumstances can be part engineered.

Bandura uses the word “fortuity” to convey the apparent nature of luck and fortune:

“Fortuity does not mean uncontrollability of its effects. People can bring some influence to bear on the fortuitous character of life. They can make change happen by pursuing an active life that increases the number and type of fortuitous encounters they will experience. People also make chance work for them by cultivating their interests, enabling beliefs, and competencies. These personal resources enable them to make the most of opportunities that arise unexpectedly.”

When I read this, examples came to mind:

Seneca grew up in Cordoba, then on the outskirts of the Roman Empire. His father sent him to be educated in Rome, knowing it would massively increase his chances in life (it did).

Picasso moved to Paris in his 20s not simply because it was a fun place to be. He knew it would put him in the same milieu as the artists, poets, dealers, and patrons who would fuel his imagination and buy his work.

Nancy Reagan first met Ronald Reagan when he was head of the Screen Actors Guild. There was another actress with her name who was a communist, and she didn’t want to be confused with her. So Nancy’s dislike of communism brought her to the attention of Ronald, known for the same anti-communist thinking.

The co-founder of Oracle, Larry Ellison, moved to San Franciso “because that’s where all the interesting people were”.

In each case we are talking about fortuity, not ‘luck’.

One more (contemporary) example, if you’ll allow me:

The director of British Museum, Nicholas Cullinan, is only 46. But he’s had a stellar career: director of modern art at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, then he ran the National Portrait Gallery in London.

Echoing Rick Astley, Cullinan told the Financial Times’ Jan Dalley (Nov. 16, 2024):

“I never had an actual plan”.

Yet after interviewing Cullinan, Dalley remarked on the following traits:

Super optimism - Cullinan loves solving old, thorny problems, like the question of the Elgin Marbles (“I start with the idea that everything is possible”);

Thinks Big - He got the British Museum job on the basis of a $50 million overhaul of the National Portrait Gallery, and is now spending over $1 billion upgrading the British Museum;

Determination - “If anyone tells me something isn’t possible, I’ll go all the more into making it happen.”

Someone who is highly optimistic, thinks on a large scale, and is unusually determined, will create for themselves a lot of ‘luck’.

They may genuinely not have a plan and yet still be very ambitious, putting themselves in places and circumstances to meet similar-minded people, throwing themselves into the crosscurrents of new and interesting ideas, and going the extra mile in their work - knowing that such behaviors tend to lead to good things. They don’t know exactly what they want to be, but they want to make a mark in an area that fascinates them.

The point is that their success does not emerge out of ‘luck’, but fortuity.

Cause and effect

You can continue to believe that Rick Astley’s success was only 9% or 20% or 30% due to his own ambition, drive, good intentions, and work - and the rest down to fortunate birth, genes, sex, ethnicity, era etc.

But there’s a detail late in his book that reveals what Astley really believes about success.

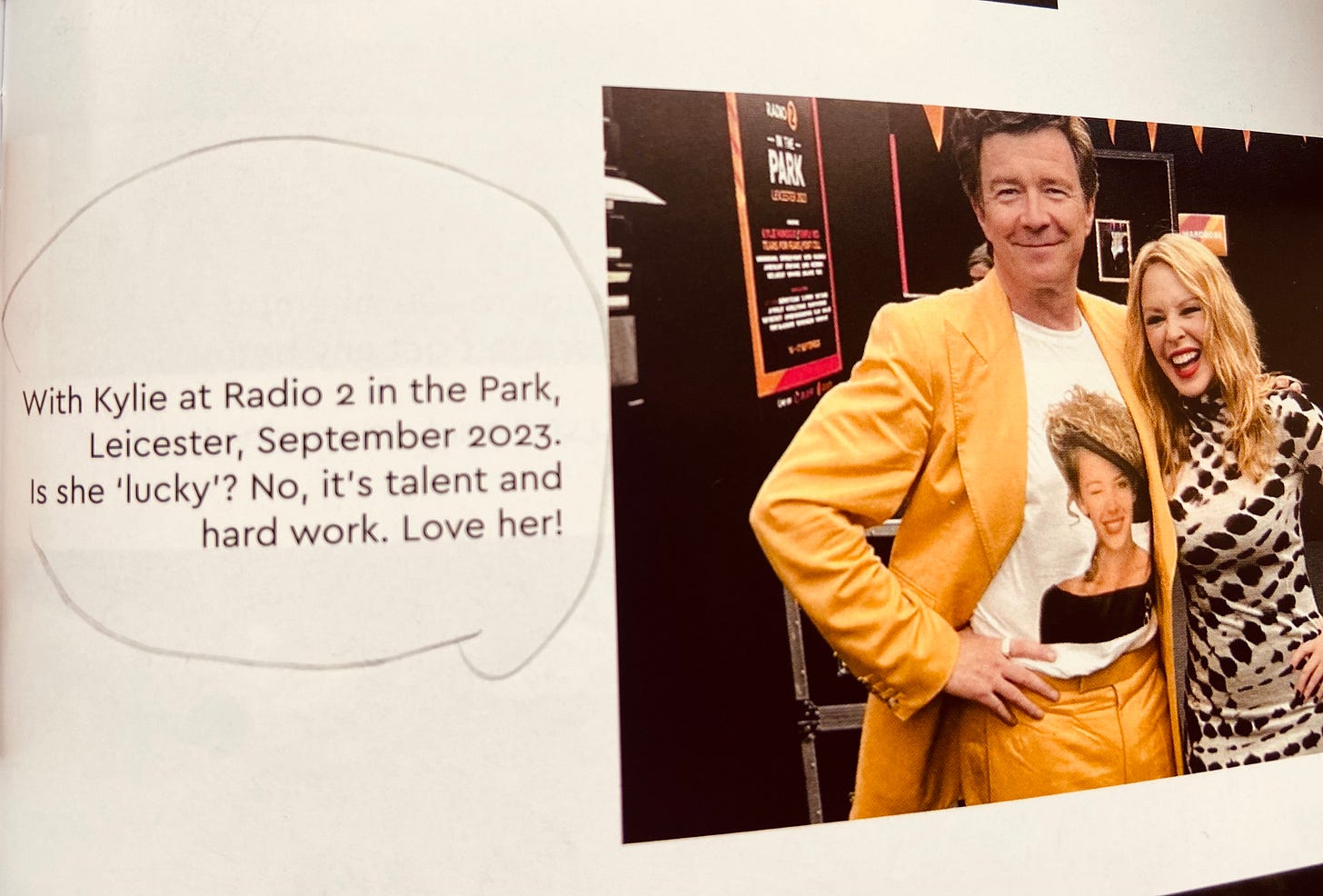

You might remember that Aussie singer Kylie Minogue had a big hit with I Should Be So Lucky, and went on to have a stellar career.

Astley and Minogue go way back, and he includes a backstage photo of them with the caption:

Is it not strange that someone ascribes another’s success to work and talent, but his own down to at least 50% ‘chance’?

I’m more inclined to believe people who say:

My circumstances were better than some, worse than others. They were a springboard. Who I am is the result of the discipline and intentions of my younger or earlier selves. Ultimately, nothing happened by chance. I take full responsibility.

Conclusion

On the final page of his General Theory J.M. Keynes wrote:

“Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist”.

We’ve all internalized some theory of success and taken it as fact - when it is just a theory.

The theory of our day is that luck and randomness are more significant than ambition, drive, talent, work, intentions, imagination etc.

What this theory does is deny cause and effect.

If you disavow cause and effect, you resign yourself to impotency. You hear yourself saying, What is the point if I don’t have the right circumstances?

It’s the mistake all non-successful people make.

Whether it’s belief in a divine being that will save you, or belief in ‘luck’, they amount to the same thing. Both are an absolution of responsibility.

Instead, be one of the ‘stupid’ ones who believes they can, even taking into account their starting circumstances, do something unusual or remarkable.

The point of life is to put your imprint on it, to bring order, quality, beauty to where there was none before.

Be for civilization, freedom, and truth.

Be against excuses, and for cause and effect.

Kind regards,

Tom

Tom Butler-Bowdon

Author of the 50 Classics series

Editor of the Capstone Classics

Find me:

Explore my website Butler-Bowdon.com with free book commentaries and interviews

NEW: AI TOM

I have a new AI alter ego

“AI Tom” is trained on my all books and content

Chat with Tom or ask a question!

Gain knowledge or ask for success tips

Text or audio

Interesting read - as usual Tom. As I was reading I was wondering when you would begin referencing Wiseman's book, The Luck Factor. I found that book excellent - and the results of some of the studies he conducted are fascinating. Finally - whenever the discussion of luck comes up I almost invariably end up thinking of that quote more often than not attributed to South African golf pro Gary Player...

"The harder I practice, the luckier I get." ⛳

Another stellar article. The role of consistent self-belief (regardless of how the external world reacts) seems to be pivotal - as Richard Koch has also highlighted in his recent work. If someone believes the universe is an immovable obstacle, it will be. If they believe it is even the tiniest bit malleable, then everything changes.